Pablo Larrain on Pinochet as a Vampire in Netflix Original ‘El Conde’

[ad_1]

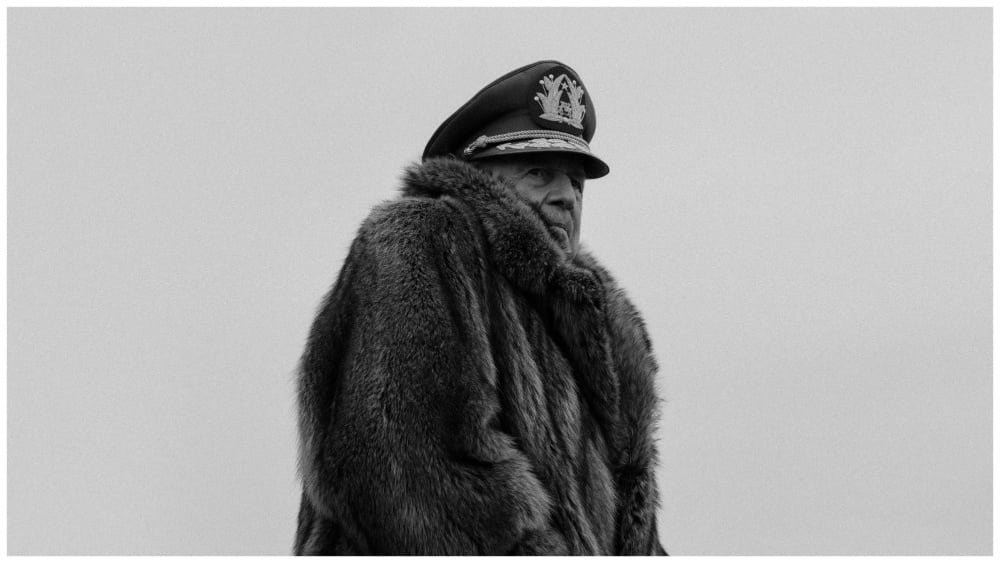

Chilean auteur Pablo Larraín is back in Venice – following “Spencer” in 2021 – with scathing satire “El Conde,” in which Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, a symbol of global fascism, resurfaces as a 250-year old vampire living in a rundown rural mansion after faking his death.

The allegorical film, beautifully shot in black-and-white by ace cinematographer Ed Lachman, stars revered 87-year-old Chilean actor Jaime Vadell in the role of Pinochet, who in reality died at the age of 91 in 2006, unpunished and rich. During Pinochet’s 17-year regime, which began with a bloody military coup in 1973, more than 3,000 people died or disappeared due to political violence in Chile, which had previously experienced a long history of democracy.

Variety spoke to Larraín – who had already tackled the topic of Pinochet in “Tony Manero” and “Post Mortem,” as well as in 2012 Oscar-nominated “No,” about the successful campaign to remove the dictator from office – and also spoke to the director’s brother Juan de Dios Larraín, a producer on “El Conde,” about the urgency to “finally put a camera straight in his face” as Pablo put it.

The Netflix original film will get a limited theatrical release on Sept. 7 in a few countries (U.S., U.K., Chile, Argentina and Mexico) and drop on Netflix globally on Sept. 15.

Pablo, I’ve read that you spent years imagining Pinochet as a vampire. Why did you chose to put him on screen in this form now? Is it because the political right is exploring new ways to conquer voters and power around the world?

Pablo: Well there is that, of course. But one of the things that also gave urgency is the fact that Jaime Vadell for me is “the” actor to play this character. And he’s in his late eighties, so it was now or I don’t know when. So he really motivated this film. And the combination of seeing pictures of Pinochet with a cape, understanding that the lack of justice [towards him] made him eternal, and then taking the big step with our company, with Juan and everyone, to make a movie that would put a camera straight to his face. It is a big step for our culture. And some people think it’s too early, other people think it’s fine.

Juan, speaking of that, I was surprised that Chile has selected “The Settlers” as its Oscar submission even before “El Conde” plays in Venice and way before the Academy deadline. Do you think this choice has to do with politics?

Ed Lachman with Pablo Larrain

Courtesy of Diego Araya Corvalan/Netflix

Juan: Well, I don’t know. But I’ve heard great things about this film. I think it’s also connected to the fact that “The Settlers” is a first work that went to Cannes, and a lot of people liked it and it’s like from a new generation, and probably the (Chilean) academy wants to see new faces and give new opportunities. So, yeah, that might be one of the answers. We don’t make films to win awards or Oscars or whatever. Of course we want to be chosen, but it didn’t happen. But I’m sure that “El Conde” will find its path and the recognition it deserves over the course of the next couple of months.

Why do you think Pinochet is still so popular in Chile today? In a vote last May Chileans rejected a proposal to rewrite the country’s dictatorship-era constitution. He still seems to have a lot of fans.

Pablo: Pinochet died in complete impunity, a millionaire, free. And because of that, I think that his figure is still like a dark stain on our society that reminds us every day how broken we are and how divided we are.

Let’s talk about the narrative tone you struck with screenwriter Guillermo Calderón. You’ve talked about a sort of “Dr. Strangelove” vibe. There clearly is this contrast between the film’s extremely satirical – and frankly, funny – aspect and the very serious matter at stake. How did you navigate that?

Well, probably the main issue when you portray someone like Pinochet and the people around him is that you need to be very eloquent about his evilness. And that’s something that cannot be negotiated. Because what happens is that once you start filming someone, there’s a natural possibility to trigger very simple empathy mechanisms. That was something that we often discussed with Guillermo. And we end up adding scenes over the initial structure where [Pinochet] would behave in the [evil] way that we thought and that expressed what he thought of the world and what he thought about other people.

I love the fact that you have an undercover nun named Carmencita as the character that ultimately tries to take him down. Is there a connection between that character and the role that the Church played in Chile when Pinochet was in power?

Pablo: During the dictatorship, the Church had an organization called Vicariate of Solidarity and it was a very important organization that helped a lot of people. Unfortunately, later, some of the people that were running that organization were involved in a sexual abuse scandal. That’s another story. But really it’s because the character of Carmencita can be fresh, funny and fascinating, and that can also be absolutely unpredictable. But, of course, it represents a power that is still strong in the world.

I want to go back to my initial question, which you sort of avoided. Is this film a response to the wind of the right that’s blowing through a large part of the world, or am I reading too much into it?

No, no, look: I didn’t want to skip the question. It’s just that then this conversation becomes very political. But I’m very up for it. What I would say is that fascism comes in different shapes and different forms. And sometimes some of them are very hard to read, because they start with seduction, then they move to fear, and then it ends in violence. And that’s something that we are seeing with the rise of the right in many countries of the world. And I guess there is an allegory in this film that can be accepted, and be felt in many societies. It’s amazing when you can talk about your town, as they say, and then you realize that your town isn’t very different from many others. So I really hope this movie can do that and can sort of break those barriers and make people think about their own realities and take this as a testimony of one of them.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Netflix

[ad_2]

Source link